Digital and social media can make public affairs more effective. But not always in the same way: depending on the environment in which an organisation operates, and its goals and challenges, strategies should differ.

Broadly, there are 3 levels of digital and social media applied to public affairs:

- Supporting day-to-day public affairs

- Digital as a campaign tool

- Digital and internal communications

Supporting day-to-day public affairs

In PR-speak, the 3 “core deliverables” of the PA professional are:

- Providing intelligence (and analysis)

- Helping deliver a message to policymakers (directly or indirectly)

- Building relationships with said policymakers and others (civil servants, media, activists etc.)

Digital and social media can support each element e.g. more efficient intelligence gathering using online tools; delivering a message via web content and search; stakeholder engagement via social networks, for instance.

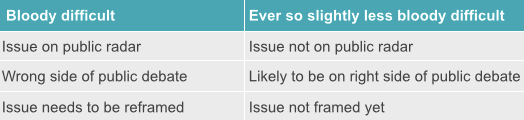

This is the nuts and bolts of digital public affairs, applicable in varying degrees to all public affairs functions and probably covers 90% of all digital PA work. It is equally relevant to organisations trying to operate under the radar, given that they are on the “wrong side of the public debate” or generally have a behind-the-scenes culture (many B2B companies) although they are less likely to engage on social networks.

Digital as a campaign tool

This is a step up from day to day support. It involves utilising digital and social media tools to mobilise supportive constituencies and generate or leverage support for a policy position. It can be done via broader use of social media and content, and online petitions, for instance. NGO campaigns, like Greenpeace’s new Detox Outdoor initiative, or a number of campaigns on sites like 38 Degrees or Avaaz, showcase digital as a campaign tool for policy outcomes.

Admittedly, most corporates do not utilise digital as a campaign tool in this way. They may be on the “wrong side of the public debate” and have no major constituencies to mobilise (e.g. banks and energy companies, say). Or the PA function may be legal/government relations centric and removed from other marketing and communications functions more adept at running campaigns of this nature.

Digital and internal communications

An oft-heard lament in corporate PA is that the function is not well understood by the business, and is as a result seen as an irrelevant cost centre and poorly funded. Digital and social media can’t magically fix this, clearly. PA professionals need to be more adept at quantifying the value of their activities e.g. how much is mitigating policy X really worth in € terms? However, improved, jargon-free internal communications by PA professionals, including internal online content strategies and better use of enterprise social networks, certainly can’t hurt.

I’ve previously summarised the tactics in a pretty(ish) visual: the digital public affairs wheel.