A little late in the day perhaps, but a quick after-thought I’d have to last month’s Copenhagen debacle is that campaigners hold more responsibility than they’d likely admit. Despite the urgency and apocalyptic tones that have been in use for years over the issue of climate change, by the time we got to 2009, the momentum in favour of doing something about it had decelerated in part because they weren’t going about their jobs in the right way.

A little late in the day perhaps, but a quick after-thought I’d have to last month’s Copenhagen debacle is that campaigners hold more responsibility than they’d likely admit. Despite the urgency and apocalyptic tones that have been in use for years over the issue of climate change, by the time we got to 2009, the momentum in favour of doing something about it had decelerated in part because they weren’t going about their jobs in the right way.

I’m not for one instant claiming that political realities – in particular, the constraints placed on politicians dealing with somewhat vague and far-away issues at a time of global crisis, and the developing vs. developed country schism – aren’t by far and away the prevailing reasons for the gridlock.

However, I’d still go as far as saying that political pressure had waned so much that politicians could go to Copenhagen without there really being anything substantial on the table – i.e. a legally binding document that demanded sacrifices of its signatories – and get away with it, in part because campaigns on climate change were often poorly executed and always disjointed. As their constituents lost interest or even became bothered by the prevalence of the issue, spurred on by an irresponsible populist press, politicians could dither: such is the nature of the game.

If we split the climate-change debate into two phases over the last decade, the first phase had a figurehead – Al Gore – who came to symbolise the issue. He carried real clout as a senior politician who had abandoned politics to focus on the one issue alone. What’s more, he approached it with a real wealth of knowledge and understanding of the science. As a result, campaigners who became involved in the issue usually did so in his shadow while adopting a serious and cerebral approach. In public consciousness terms, the issue was escalating fast and the doubters weren’t too comfortable about raising their voices.

Phase 2 began once Gore stepped out of centre-stage, transforming the issue into an exercise in jumping on the bandwagon. All of a sudden, reducing one’s carbon footprint was the de-rigueur do-gooder issue for all organisations. Scientific argumentation got lost in the muddle as second-rate celebs pleaded with us to ride our bikes. Similarly, the lack of a focal point for the campaign meant it became disjointed: every oil and gas giant had its own separate campaign; it seemed every pressure group was doing its own thing too. Single-issue campaigns propped up everywhere but seemed to have different messages and I personally was never quite sure who was behind them. Lots of these campaigns were very good in terms of output – Kofi Annan’s tck tck campaign looked especially crisp and garnered a lot of signatures, although it came too late in the day – but there were simply too many overlapping initiatives rather than a single, strong, global voice spurred on by a number of interconnected campaigns. Result? The real message got lost and the populist press turned the issue into yet another fashionable and elitist pursuit for politicians detached from the man on the street.

Is all lost? No, mainly because the issue is real. What’s more, with the crisis diminishing, more people may start thinking beyond their day-to-day to issues outside their backyards. And with regards to campaigns on climate change, I think we’ll see a shift. Organisations who have hopped on the climate change bandwagon (or any other issue for that matter) are being scrutinised evermore by cynical consumers wary of greenwashing and will have to prove that they are serious about playing a positive role, while pressure groups should increasingly seek to join forces. This should result in better, more low-key, integrated campaigns by a number of public and private players, involving stronger grassroots engagement and mobilisation. Hopefully, this will put renewed pressure on the political class and ultimately result in responsible action, not hesitation.

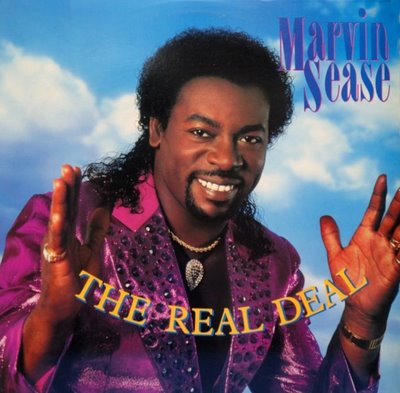

Image source

Digital advocacy has been effective on issues that capture the public imagination because the web is an effective grassroots mobilisation tool. From whale hunting to GMOs, pressure groups and concerned citizens have expressed anger, spread the word and mobilised likeminded people. Were Greenpeace to announce a big-time campaign tomorrow on, say, mink farming in Europe, it could be web-centred, with offline elements operating around it.

Digital advocacy has been effective on issues that capture the public imagination because the web is an effective grassroots mobilisation tool. From whale hunting to GMOs, pressure groups and concerned citizens have expressed anger, spread the word and mobilised likeminded people. Were Greenpeace to announce a big-time campaign tomorrow on, say, mink farming in Europe, it could be web-centred, with offline elements operating around it. A little late in the day perhaps, but a quick after-thought I’d have to last month’s Copenhagen debacle is that campaigners hold more responsibility than they’d likely admit. Despite the urgency and apocalyptic tones that have been in use for years over the issue of climate change, by the time we got to 2009, the momentum in favour of doing something about it had decelerated in part because they weren’t going about their jobs in the right way.

A little late in the day perhaps, but a quick after-thought I’d have to last month’s Copenhagen debacle is that campaigners hold more responsibility than they’d likely admit. Despite the urgency and apocalyptic tones that have been in use for years over the issue of climate change, by the time we got to 2009, the momentum in favour of doing something about it had decelerated in part because they weren’t going about their jobs in the right way. Yes I love it, but not because it can give a face to a stand-offish organisation, humanise it, make it more approachable and the rest of them ol’ chestnuts. These are the very positive byproducts, but the real root of why blogging is brilliant lies in the flexibility it offers.

Yes I love it, but not because it can give a face to a stand-offish organisation, humanise it, make it more approachable and the rest of them ol’ chestnuts. These are the very positive byproducts, but the real root of why blogging is brilliant lies in the flexibility it offers. Before this post, I hadn’t blogged for two weeks; and looking at my output over the last few months, it’s been pretty infrequent and not especially inspiring stuff by and large (not that I’m by any means claiming to have written super inspirational stuff on a regular basis before then, but you get the gist.) Why is that? 60 hour weeks and plenty of travel, in short. Problem is, I HATE that excuse. So f’ing what if I’m working hard? A post can be ten lines long. I could blog while I travel, I could get up 2o minutes earlier in the morning and write a post or likewise go to bed 20 minutes later. That’s where I’m a hypocrite. I frequently tell clients who claim that they just don’t have the time and resources to engage online that they DO have the time: if they value its importance and what it can do for them, surely they can add a half hour here or there into their oh so busy schedules. And if they really can’t, sleep a little less, cancel the game of golf, or – heaven forbid – cut a meeting short.

Before this post, I hadn’t blogged for two weeks; and looking at my output over the last few months, it’s been pretty infrequent and not especially inspiring stuff by and large (not that I’m by any means claiming to have written super inspirational stuff on a regular basis before then, but you get the gist.) Why is that? 60 hour weeks and plenty of travel, in short. Problem is, I HATE that excuse. So f’ing what if I’m working hard? A post can be ten lines long. I could blog while I travel, I could get up 2o minutes earlier in the morning and write a post or likewise go to bed 20 minutes later. That’s where I’m a hypocrite. I frequently tell clients who claim that they just don’t have the time and resources to engage online that they DO have the time: if they value its importance and what it can do for them, surely they can add a half hour here or there into their oh so busy schedules. And if they really can’t, sleep a little less, cancel the game of golf, or – heaven forbid – cut a meeting short.