I just re-read my last post and wanted to expand a little on the challenge that is PA and digital in Brussels especially. Using the full array of digital is tricky on a number of levels, of which I’d cite three in particular.

1. Limited “critical mass” on most issues

Digital is always relevant in some way. Even with an audience of 20, the 20 will use Google to access information and will expect an organisation to have good material on their website (or at least relevant and up-to-date material). So content and search are always essential.

However, the true and game-changing value of digital lies in the speed and ease of engagement, and on this front i.e. engaging on issues online, there isn’t much going on. Part of the reason is that on a number of issues, the number of players involved is tiny, and even a successful online micro-community requires at least say 30-50 people who are highly active (ideally far more). Plus the community should include a suitable array of players. On issues, this would be, say, government (national and Brussels), industry and civil society. Yet on many issues which PA professionals work on, at least one significant player will be absent online (i.e. perhaps industry and some national-level civil society are active, but no one on from the government side, or vice versa). Online engagement then becomes like a concert where a headline act has failed to show up: a bit pointless.

Another element has an impact on the limited mass on Brussels issues: the paucity of links between online conversations at national and EU level. I’m not going to get into why it’s the case (language, parochialism, basic lack of knowledge of what others are doing etc.) but the fact of the matter is that if PA issues were seen in a pan-European light, digital might offer a platform for broader conversations and help build up critical mass. As it stands, Brussels issues too often remain Brussels issues, unaffected by activity at national level.

2. The nature of (some) issues

I’ve touched upon this in the paragraph above to some extent: niche regulatory issues discussed in Brussels are often not of interest to larger groups of people, meaning that the critical mass needed for active conversation online is simply non-existent.

The point about the nature of the issues goes a step further though. In many cases, PA professionals don’t want to or simply don’t have the consent to engage on issues “in public” – which the web essentially is even if a conversation is confined to a micro-community. And it’s not because they’re shady operators trying to elude the public, but because there are often complex legal, competitive and political ramifications that need to be resolved before an organisation can go public.

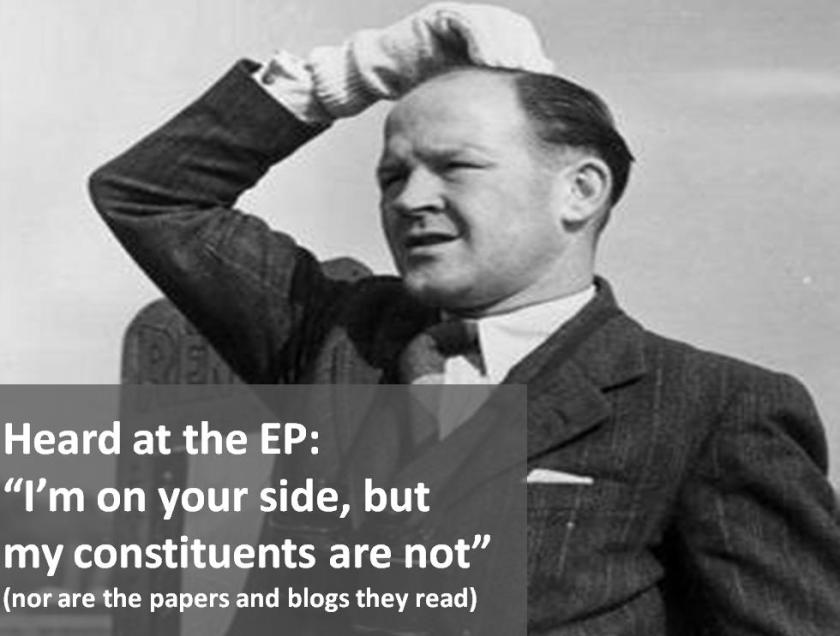

3. The PA professional

I can’t count the number of times a condescending PA pro has implied that digital is irrelevant in Brussels and should be left to the marketers and consumer PR folk, the fallacy being that digital is a mass market medium. It’s not, and anyway, digital is only part of the parcel of how a broader, more integrated approach to PA is increasingly required to ensure success in Brussels (see a previous post on this here.)

However, these developments require an appreciation of and an interest in integrated communications as a discipline: the ability and willingness to analyse a wider set of audiences, to explore and utilise new channels. Too often, the PA professional does not view him or herself as a communicator, but rather, would prefer to be defined as a political scientist, policy counsellor, regulatory expert, or a lawyer even. Undoubtedly, the skills required to be any of these remain key to PA success, but on their own, they’re not enough if the people in question fail to embrace communications more holistically, whether on or offline.