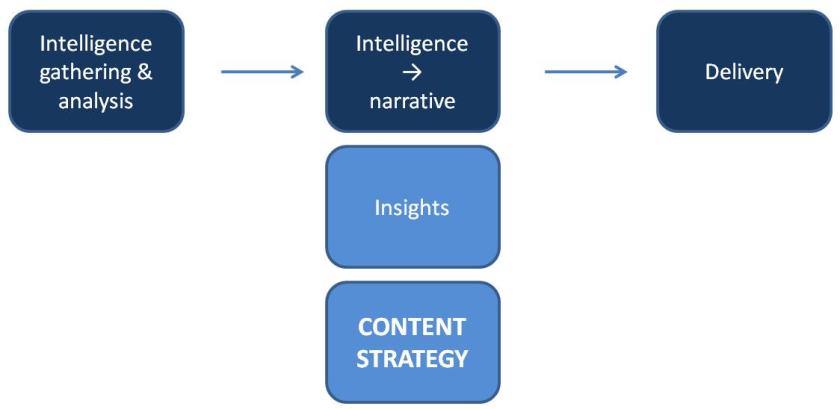

I use this image frequently when presenting on how Public Affairs is developing in Brussels (usually in the context of Public Affairs and digital specifically). It’s not a particularly novel or intricate notion: campaigners/pressure groups, have influenced policy making beyond what their resources should have permitted because they have told a better, and simpler, story. They’ve aligned with public opinion – and later driven public opinion – sometimes by pulling at the heart-strings, always using compelling, simple messages, oft-repeated – and plenty of visualisation. In the PA context, industry has famously been poor at doing just that: telling a simple story that resonates with people – including policy makers.

There’s usually a fair bit of nodding in the room at this point followed by one or more of the following inevitable rebuttals:

- Yes, but you see, they can get away telling tales, we can’t.

- Yes, but you see, our customers, directors, etc. expect us to be credible, scientific, cerebral, fact-based etc.

- Yes, but you see, we can’t talk openly about our issues, they’re tip-top secret.

Tosh. The suggestion that pressure groups merely make up tales which gullible folk fall for is overemphasised. It happens, sure, but you need to give them more credit. Pressure groups do their groundwork: analysing audiences, developing storylines based on insights gained from their analyses, testing messages, delivering them through multiple channels and multiple forms of media with a fairly good inkling that they’ll succeed. They don’t do every issue, or attack every opponent: they focus on where they’re most likely to win.

Also, being story driven rather than fact driven need not imply fluff: it can simply mean talking about issues in an everyday context, openly and honestly, using real people, and language which people understand. It implies dropping the condescension and perhaps showcasing information in summary form or visually. It can mean talking to local community leaders and retirees rather than just policy-makers and the FT about things which resonate with them. In short, communicate about things people care about, in a language they understand, and be nice doing so.