Volumes could be written about this, but at its basest, the argument is this. In pre-digital, the only way to reach considerable numbers of people direct was via advertising. Positioning and branding were heavily reliant on advertising; if you wanted to showcase the real you, be fun, be smart, use visuals etc. you would advertise. Now, in the digital age, you can reach your target direct; you can do all of the above without buying media space. What’s more, you can do so while engaging: hearing what people have to say and building relationships with people who matter. Is advertising obsolete? Of course not, but it’s not all-dominant and can’t stand alone anymore: it needs to be intertwined with relationship building. And that’s where traditional advertisers are struggling in the digital age (and incidentally, where smart PR companies are thriving.) Their age-old love it and leave it approach to campaigns hasn’t yet developed into one in which advertising and PR/stakeholder relations are integrated. That needs to happen if they’re to ensure long-term survival.

Category: Social Media

Thou shalt not speak funny… Instead, write like Bono and you’ll be fine

I met Kattebel at the recent Web2EU event and she remarked on my recent post in which I state that communicators tend to write in an “over-the-top, pompous, formulaic manner.” A real no-go on the web in particular.

She (rightly!) said that I should perhaps have given some pointers on how to best write for the web rather than merely criticise others for being dull. Instead of producing a list I’ll do so by pointing to a post I found amongst long-lost items I have saved on Delicious: click here to read it. It’s a dazzling tribute to how to best write for the web (although it probably wasn’t really written for the web specifically, but never mind.) Love it: personal, from the heart, direct and honest (and by Bono no less.) OK sure, most people would get the boot if they were to adopt his style on their company blogs, but you get the gist.

p.s. Looking through some of my own posts, I found a few in which I touch upon best practice for producing content for the web. Not quite Bono-like but hopefully helpful to someone out there:

Avoiding fluffy CSR

However much the C-Suite wants it to, fluffy CSR doesn’t work in PR. If you send a press release about your organisation’s new initiative to save a whale or help local school kids cross the road, it’ll get binned. .

In the digital age, organisations can communicate directly to their audiences. Unfortunately, plenty of communicators are squandering the opportunity by adopting the same approach that doesn’t work with media. They talk about their fluffy initiative (aforementioned whale, kids etc.) and leave it at that. Media doesn’t cover it for a reason: their readers don’t care. They won’t care now that they can access the content directly online.

When might they care?

When tangible effects and benefits are highlighted. So you’ve trained someone? Given something away for free? That’s not the story. The story is what happens next. Proving that the freebie or the training has had an impact.

When you treat people like grown-ups and admit you have a stake in your own CSR. Initiatives like Pepsi Refresh are criticised because they are mere gestures unrelated to the business itself. We live in cynical times: only action that benefits the community as well as the organisation responsible for it will be deemed truly authentic.

What to do about angry commenting trolls: ignore them

“Too many voices, too much scattered, illogical, ill-considered criticism.” Written in 1920 by F. Scott Fitzgerald about literary critics (a million apologies for the snooty literary reference.) How would the great man have felt about trolls who seem to spend their lives visiting websites and blogs that don’t moderate to write irate and often irrational comments? They’re everywhere. My favourite news-site – http://www.guardian.co.uk – has a great section for non-affiliated bloggers called Comment is Free, but you’ll be hard pressed to find smart back-and-forth between informed readers in the comments following any article about politics, global warming or what have you. Instead, you’ll largely find angry right-wingers spouting bile rather than offering constructive remarks. Even my own humble blog got the works last year in response to a rather innocuous post about the quality of Nespresso coffee: highly recommended for a laugh (the comments, not the post.)

“Too many voices, too much scattered, illogical, ill-considered criticism.” Written in 1920 by F. Scott Fitzgerald about literary critics (a million apologies for the snooty literary reference.) How would the great man have felt about trolls who seem to spend their lives visiting websites and blogs that don’t moderate to write irate and often irrational comments? They’re everywhere. My favourite news-site – http://www.guardian.co.uk – has a great section for non-affiliated bloggers called Comment is Free, but you’ll be hard pressed to find smart back-and-forth between informed readers in the comments following any article about politics, global warming or what have you. Instead, you’ll largely find angry right-wingers spouting bile rather than offering constructive remarks. Even my own humble blog got the works last year in response to a rather innocuous post about the quality of Nespresso coffee: highly recommended for a laugh (the comments, not the post.)

In my line of work, this issue props up all the time. We’re always talking about the value of two-way conversations and how it has revolutionised the world of comms and the nature of how organisations and politicians are expected to engage; but then clients rightly ask questions along the lines of… Are trolls not compromising conversation? Are moderates in search of conversation getting crowded out? And most of all… Do negative comments by angry sociopaths not reflect badly on our organisation?

Now this may not be entirely de-rigeur but my recommendation tends to be that organisations should be quite selective in terms of moderation. Plenty of social media “experts” will claim that you need to be completely open and let everything through because it’s transparent and democratic; what’s more, it’s supposedly a reflection of public opinion and so organisations should just accept it. I totally disagree. Take Comment is Free. I’d say at least 70% of the comments are angry and written by staunch right-wingers. That doesn’t reflect public opinion anywhere! The angry and the slightly dysfunctional are always going to make more noise and letting them all through the door will kill debate.

So what’d I do? Frankly, what most smart organisations have chosen to do: “moderate in moderation.” Have a strict code of conduct that clearly states what you will and will not permit but do allow for plenty of criticism as long as it’s in full sentences and constructive. In that case an organisation has a chance to hear about real concerns and perhaps even do something about them; and they’ll be able to respond with their side of the story and build relationships with supporters and critics alike without being crowded out by trolls. The essence of online engagement.

Contrasting storylines on and offline

I’ve been conducting some research over the last week to compare an issue in traditional media and online. Three key observations as follows.

First, the traditional news-cycle is obviously shorter than the online story cycle, but it’s always surprising to see just by how much that is the case on most storylines. A story can have traction online over the space of months while it dies after a couple of days in the papers: testament to the word of mouth (and mouse.) Sometime it’s ongoing discussion of an issue but other times it’s someone “breaking” the story for the umpteenth time: in the online age, a risk-factor remains a risk-factor for far longer than you’d want.

Second, although the stories hitting the newsstands and the online space are usually aligned (albeit with timing disparities as described above,) some stories that are huge with the press hardly make headway online (and vice-versa). Confirmation that the media isn’t the sounding board of public opinion as much as one might expect (but also that online buzz doesn’t necessarily bother journalists that much – but more on this below.)

Third, the media always came first. Although we keep hearing about stories being broken on Twitter while the presscorps has been utterly oblivious – a trend which is definitely on the up – it’s fair to say traditional media is still likely to break a story first on the majority of issues. However, this does not detract from the importance of the web in the way stories come about or spread. Besides the actual breaking of news, I think the main trend (although I didn’t come across it in this case) will be dormant issues brought back to life by the press once they’ve spread like wildfire online.

A key to comms success: accepting the personal/professional grey area

Open, honest, humble and transparent communication is the order of the day. Organisations need to abide by this mantra or risk losing the goodwill of customers, constituents and regulators alike; just look at the Toyota debacle, in which their poor PR response has taken more of a bashing than the faulty cars at the root of the issue.

A big part of my job lies in helping organisations harness their internal expertise in a manner which resonates with their audiences. Meaning, get them to communicate themselves rather than doing it for them or trying to coax others into doing so (i.e. media.) But what is as important as the actual substance of their expertise is to abide by the “medium is the message” maxim, meaning that how they communicate is as important as what they’re actually imparting.

For this to really work however, people who communicate on behalf of organisations must accept the personal/professional grey area: the two must not be mutually exclusive anymore. Given that audiences expect open, honest and humble output, a highly structured and corporate style of communication will not usually be effective, whatever the message. Communicators need to offer at least a glimpse of the personal if they are to be credible. And no, this doesn’t mean that CEOs should be showing their holiday snaps to clients; rather, output should have a name on it, and that name should showcase a personality that is more akin to what it might be like in private than any archaic set of rules governing corporate communications in a bygone age.

In short, be yourself. Sounds easy, right? It’s not. Many people feel uncomfortable showcasing their personality in a professional setting, while many, many others can’t get their head around it even if they’d love to let go. If speaking on behalf of an organisation, they believe that they need to “speak funny” to be credible.

Fret not however: we are gradually seeing a change, and the dynamics of it are very interesting. Seeing the damage that solely sticking to the old-school model is causing, people on top of the food chain are appreciating the value of a more open, personal and informal manner of communicating. Meanwhile, younger people who have practically grown up with the web and view the personal/professional grey area as a reality are increasingly making the grade within organisations. Last up, the dullards in the middle. Wake up!

The bane of the online communications consultant

It’s fun, it’s effective, it’s multifaceted and it’s on a steep upward trajectory. All in all, in Brussels and elsewhere, helping clients navigate the online space is a pretty good thing to be doing right now. But it’s a double-edged sword in some ways:

- The implementation part has so many variables that it’s easy to get bogged down in dull, irrelevant nitty-gritty and lose track of your true objectives. Sure, you need to get things right, but often, strategic communications veers too far into sheer project management. The key here is to keep the role of the strategist and the project manager separate, and for the strategist to have more visibility.

- One of the keys to a successful communications programme is integration. What you do online and offline should be closely aligned, but it’s often hard to get right because of the way communications teams are structured. Web, regulatory and media people are all kept separate, and as hard as you may try to put everyone around the same table, it often doesn’t happen. On the consultant side, discipline is also important here. You may understand the web inside out and be tempted to overlook the other stuff. Don’t do it.

- Closely aligned to this is appreciation of the web consultant as a communications professional (my pride takes quite a hit sometimes on this…!) With some clients, it’s an ongoing struggle to remind them that online communications is primarily a strategic exercise, not a technical one. You have more in common with the business, regulatory, marketing and communications people than IT. All credit to IT, but they do something entirely different.

- Then there’s the web doubters on the client side; people who aren’t quite sure of the value of online communications. Advocacy and media work have worked for years and are still relevant today, so why fix it if it ain’t broke? The fact is that the model is, if not broken, in need of an upgrade: old-school tactics are still relevant, but they need to be backed up. People are a lot more cynical, opinionated and engaged than ever before, and a well-executed online programme will help you cater to this part of the equation and in turn make your media work and advocacy more effective. As a consultant, what do you do about the doubters? You treat the sell as ongoing: you constantly have to re-explain the concepts, what you’re doing and why it will work. And most importantly, you need to identify your eChampions on the client side who strongly support what you’re trying to do and will mobilise on your behalf and join the challenge to win over the naysayers.

- There’s the web doubters, but there’s also two types of know-it-alls that often present a challenge. First, the old-school communicators who treat the web as just another channel and simply transfer their understanding of the offline world to it. They think a website should look like a brochure; that a blog entry should be structured like a press release; or they’ll struggle with two-way nature of the web and simply use it as they would a megaphone. Second, there’s the (usually, but not always) junior communicator who has been handed responsibility for online comms because they like technology and are comfortable with it. What often arises in these cases is that they act as if they’ve got a new toy and spend lots of time setting up Facebook fan pages and tweaking things in Photoshop, but they’ll do nothing to help you reach your communications objectives. In fact, they may even be detrimental in that respect. What to do? As in the point above, the ongoing sell – or ongoing education even – becomes essential.

And a final point. The web is big and complex; it’s all happening so FAST; you need to keep track of the other channels AND try to keep up to date with the issues; and you need to deal with the points cited above – in particular the ongoing sell. To get it all right requires a lot of patience; and you’ll need to read a lot every day to stay on track. But it’s worth it in the end.

“I don’t get Twitter”

I hear it all the time, and admittedly, it’s not the easiest thing to provide a clear and tangible response to. There’s scores of reasons why Twitter can be important to organisations: learning from and building relationships with individuals and other organisations with similar interests; tracking issues in real-time, in turn enabling appropriate analysis and response to consumer, constituent or other stakeholder concerns.

However, when explaining it to people who are not communicators or avid web users, and who would no doubt struggle to contextualise, that all sounds a bit bland. What I find works best as an explanation in these cases is contextualising within someone’s own personal interests. Ask them what they’re into and, say, if they cite Italian cinema, ask them to imagine connecting to 1,000 other people from all over the world who are really into Italian cinema in an offline setting. A film festival perhaps.

On Twitter, they can connect to these same 1,000 people. In one place, they’ll be able to track what these 1,000 people are saying and items (articles, reviews, screenings) they are providing. As a follower they have the option to simply observe and learn: a non-stop incoming stream of valuable information they’d otherwise have to read 100 websites and magazines a day to keep up with. If they then fancy engaging further (which they should) they can provide this community with their own input, respond to what others are saying and engage in conversations.

So you’re essentially placing Twitter within a real-world framework. Doing that will make it seem a little bit less like technical mumbo jumbo and more about human interaction, which is what Twitter and social media at large are all about: they’re spaces that allow for people to connect, not the playing fields of techies, teens or social recluses. And that’s really the key message to transmit to the doubters.

Integration is king (and a word about online targeting)

Weber Shandwick recently ran a survey in which they found that UK consumers under the age of 35 are far more likely to be influenced by newspapers than those over 45. By some margin too. So the myth that younger people consume endless amounts of online media but won’t ever be reached offline can safely be dismissed. Another feather in the cap for an integrated approach to communications.

Slight tangent on the topic of demographics and the web: I’d urge you to have a look at Forrester’s Social Technographics graph, which showcases internet users’ behaviour based on how they consume and produce content online, from those that merely read, right through to those who regularly publish. Forrester also have a consumer profile tool which allows you to view the data based on various age groups, sex and country (13 so far.) What am I getting at? That traditional demographic trending used in marketing goes out the window when it comes to the web. If you’re an organisation looking to reach a certain target group online, choosing the right message and channel – and the sort of engagement or other behaviour you can expect – is a far more complex exercise than you might previously have imagined, and requires some skill to get just right.

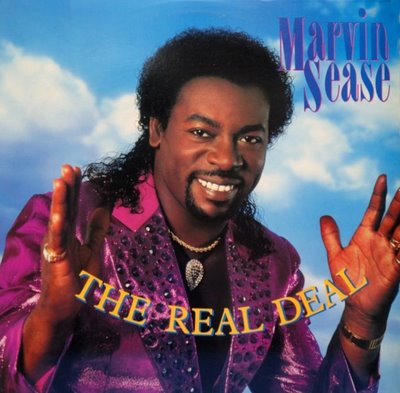

Digital advocacy nearing the real deal

Digital advocacy has been effective on issues that capture the public imagination because the web is an effective grassroots mobilisation tool. From whale hunting to GMOs, pressure groups and concerned citizens have expressed anger, spread the word and mobilised likeminded people. Were Greenpeace to announce a big-time campaign tomorrow on, say, mink farming in Europe, it could be web-centred, with offline elements operating around it.

Digital advocacy has been effective on issues that capture the public imagination because the web is an effective grassroots mobilisation tool. From whale hunting to GMOs, pressure groups and concerned citizens have expressed anger, spread the word and mobilised likeminded people. Were Greenpeace to announce a big-time campaign tomorrow on, say, mink farming in Europe, it could be web-centred, with offline elements operating around it.

However, the vast majority of advocacy issues don’t capture the public imagination: nobody cares; media pays no attention. Until a short time ago, these were the sort of issues where advocacy was done off the radar i.e. primarily with stakeholders and policy-makers sitting down face to face. There’d be no large-scale media campaign or the like in support because it wouldn’t have been worth the effort seeing as all stakeholders were a phone-call away.

Digital advocacy is now nearing the real deal for niche issues as well. It is ubiquitous enough – even in public policy land (see Fleishman’s EP Digital Trends or Edelman’s Capital Staffers’ index) – to work as a direct advocacy tool.

In practice, if you plan and execute the online element of your campaign well, you can safely assume that you’ll reach relevant policy-makers directly, as well as engage and/or mobilise the aforementioned stakeholders that are just a phone-call away, using primarily online channels. By no means does that mean that traditional advocacy or media relations are a dying breed, but they can now be supported, enhanced and sped up no end. Exciting times ahead.